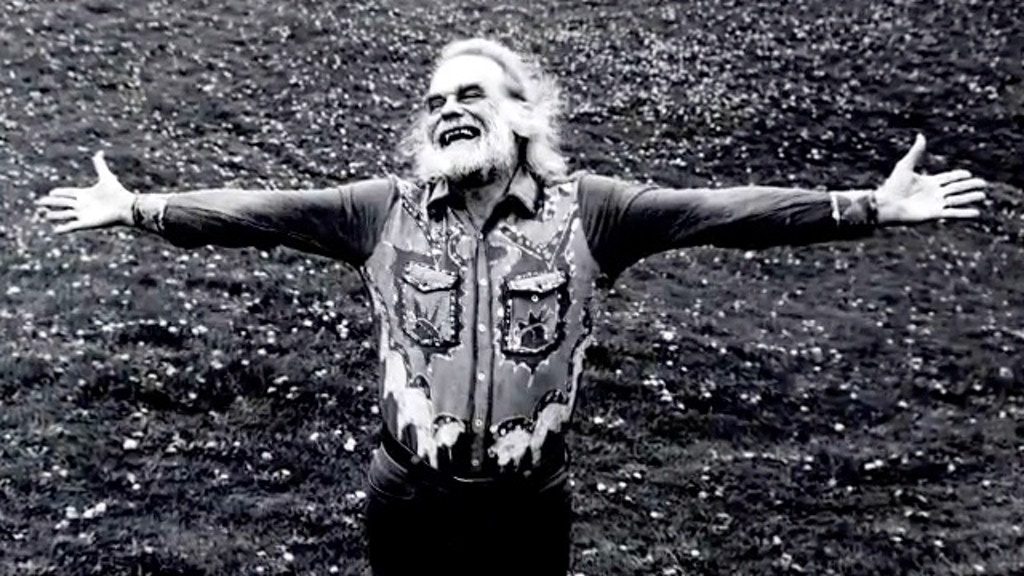

James Broughton (1913-1999) was a poet, writer, artist and filmmaker who was part of the San Francisco Renaissance, which preceded Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and beat movement.

The documentary (and website) Big Joy depict the big life of this big creator who never ‘sold out’, but rather always chose to stay true to his passion. Following a successful screening of one of his shorts, The Pleasure Garden, at the Cannes film festival, Hollywood came calling. But he chose instead to stay with his roots and keep making independent films.

Here’s the trailer for Big Joy:

Here’s The Pleasure Garden and a few of his other short films, available through The James Broughton Cinema YouTube channel:

And here’s another short documentary about Broughton:

And his beautiful approach to dying:

• • •

In his essay “The Alchemy of Cinema”, from his book “Seeing the Light“, Broughton beautifully captures the magic and mystery of the creative process. You can see a PDF of the whole book here.

Here is the essay from the book, which is now out of print.

• • •

The Alchemy of Cinema

“Concoct an observable eternity.” – Thomas Meyer

Film has its own peculiar alchemy. This is inaptly called Editing. In truth it is the real opus of cinema.

In the editing laboratory takes place the most crucial and often the most creative part of making a film: the alchemical mystery.

Alchemy is the ancient art of transforming the raw matter of nature into a valuable essence. Sometimes, though rarely, this emerges as precious gold. Usually the alchemist is lucky if he gets quicksilver. But this is an appropriate enough element for the silver screen.

*

Walt Whitman reassures us: ‘All truths lie waiting in all things.’ The alchemical adept puts his raw material through many changes to rid it of ‘impurities.’ What he seeks is a solid substance of ineffable value, something ‘indescribable and inimitable’-which is how Renoir père described the quality of a great painting.

What can scissors and glue do?

Let us juggle and join and juxtapose!

O what scissors and glue can do!

*

The cinematic alchemist works in the dark of his laboratory for hours, days, months, years, seeking the seemingly impossible task of metamorphosis. With his various paraphernalia he tries to transform the invisible into the visible, or as Redon said, to ‘put the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible.’

He searches for that continuously flowing Light which will transform leaden fragments into one glowing jewel. Often enough, alas, his ‘original chaos’ remains unredeemed.

*

Of the editing process Cocteau said: ‘To reorganize chance. That is the basis of our work. ‘

*

Alchemy is the art of Hermes, the great shape-changer. In the editing laboratory Hermes turns the film into the shape of an authentic illusion.

The Humanist Patrizi proposed to Pope Gregory XIV: ‘Let Hermes take the place of Aristotle!’

*

At my very beginning, with The Potted Psalm I learned that no two individuals edit the same footage in any similar way. Every man sees the world arranged to confirm his vision of it. Our joint footage Sidney Peterson abstracted with an emphasis quite different from my own version. Not only were two aesthetics and two mother complexes at variance; we were also two different kinds of alchemists. All alchemists might start from the same raw material, but each would end up with a unique philosopher’s stone.

*

Alchemy is seeing into what is not yet visible.

It is a uniting with the incomprehensible that wants to come into being. It is to discover a microcosm.

It is to release the David hidden in Michelangelo’s stone.

It is to unclothe the Inevitable.

‘All things are beautiful if you have got them in the right order,’ said John Grierson.

*

With the putting together of Mother’s Day I ventured deep into the alchemical mysteries of film. The completed footage hung for weeks in the bedroom of the Baker Street flat I shared with Kermit Sheets. Night after night the strips of film rustled in the breeze from the open window as I lay awake listening to them, wondering how they would ever fit together, waiting for them to tell me how they would most like to be arranged in time. I had no frame of reference. During the shooting the original plan of the film had turned into something utterly different, something I did not understand but recognized was necessary. Eventually I sat at a dinky Craig viewer hour after hour learning the images, seeking their hidden correspondences, gradually discovering the structure. It was like the unraveling of a secret formula. I was more surprised than anyone by what emerged. And enormously grateful to the Guardian Deities who had made it happen. (They, I find, only like things that are allowed to grow into their true inevitability, they pay no mind to readymades.)

‘Everything should be as simple as it is, but not simpler,’ said Albert Einstein.

*

The public is only able to see projected films, the poet of cinema has to see the unprojected ones.

I love going to the editing table. It is an altar of mysteries. Dust it off devotedly. Let us consecrate. At any moment a temporal ecstasy may occur.

Is this why professional film editors have the tranquility of priests whereas their missionary brothers out shooting wear a more worried look? Editing is a form of midwifery in which one is confident that some sort of new creature will eventually be born.

Chaplin told Cocteau that after making a film he ‘shakes the tree.’ One must only keep, he added, what sticks to the branches. People who like puzzles make good editors. An emerging film is a diagram-less crossword, a jigsaw without a known shape. Sometimes it is the trial and error of a labyrinth. As Leonardo da Vinci put it, ‘You have to go up a tunnel backwards.’

*

Wagner wrote of Beethoven: ‘All the pain of existence is shattered against the immense delight of playing with the power of shaping the incomprehensible.’

*

Requirements of the alchemist: passion, perseverance and prayer. Some of the greatest raptures of cinema occur at the editing bench when an unexpected felicity emerges that is so right and inevitable that one knows one has touched a truth. This is the Eureka moment: the flower has appeared in the stone. A finished film is composed of many such felicities, but they are so absorbed into the structure of the total work that they are taken for granted by the spectator as mere building blocks.

Blake: ‘It takes all of creation to make a single flower.’

*

Practically speaking cinema is: putting images together in various musical measures. Editing is the music of cinema, as music is the architecture of time. Editing gives film its form, notation, counterpoint, development, pace, syncopation and style. Such an alchemy should be spared the censorious term of Editing. The art is that of Composing. To edit film is to compose eye music. When you edit do you know what key you are in, what your signature is, what your measures are?

*

In order to qualify as alchemical adepts, all novices in the Brotherhood of Light are required to study music. (This has nothing to do with listening to records while drinking beer with friends.) Thus you will learn how to observe your film running through the viewer as a musical notation rather than merely a succession of scenes. This will reveal your form, your measure, your long and short notes, your rests, your intervals, your rhythms. You will discover how much the composition of a film relies on its metrics. Thus you can better enjoy what goes on in, for instance, A Movie (Conner), Arnulf Rainer (Kubelka), Scenes From Under Childhood (Brakhage), and Breathing (Breer). If you ain’t got rhythm, you’ll never make it.

Vertov: ‘The essence of film is in the interval.’

In music the interval is the fixed relation between two notes. The camera creates fantastic motion in the intervals. In Editing you create even more fantastic motions between the shots. Have you digested your Vertov, not to mention your Eisenstein?

Learn from the best, learn from the masters. If you are a swan, don’t hang around ducks. When he went to study modern composition under Schoenberg, John Cage was surprised that the pieces studied were Mozart sonatas.

*

In music any theme can be given whatever tempo and key you want. Similarly you can cut your filmed scene fast or slow; the image will convey its action either way. First, if you like, edit what the pictures are doing. Then recompose the whole thing metrically.

Cinema is a form of opera. Learn your notes. Count your frames. Articulate your rhythms. Phrase your line. Shape your tone. Measure your rests. Practice harmonics. (Is your superimposition a major or a minor chord? A staccato or a resonance?) Question: If there are 24 frames per second, how many frames per minute do you have to play with?

Furthermore in this medium of durations don’t neglect to measure the timeless as well. Great alchemy moves with the primordial rhythms of The Only Dance There Is.

*

Is cinema a Byzantine art?

Putting a film together resembles most of all the art of mosaic. These myriad ’tiles’ of image, all the same size and shape in your hand, have to be trimmed, arranged, carefully placed, and glued together to make a total picture. But unlike The Wedding of Theodora a film mosaic is never seen in toto. Film is a mosaic on a spool which reveals its total luminosity only after it has been unreeled through Light. It is a mosaic in duration, many pointillist fragments in succession, totally present only when it has disappeared into darkness at The End. Like a symphony.

Hence in composing film we have a craft that might be called Musaics. Do you qualify as a musaicist?

Broughton’s Musaic Law: Thou shalt glue thy vision note by note until it dance the Light.

*

Some Mottoes for Editing Room Walls

Compose yourself. Then compose.

Every frame is a moment of Now.

Take nothing for granted.

When in doubt, cut.

(Barbara Linkevitch revised this to rhyme: When in doubt, cut it out!)

Attain the inevitable.

*

Some Useful Pinal Tests

1) Look at your film upside down. This not only gets some blood into your head, it will show you how well your work hangs together. You may also discover that it is really one for the bats.

2) Look at your film with your back. With a mirror, watch your film projected over your left shoulder. This will not only show you what a mirror sees, it will test the sturdiness of your compositions.

3) Look at your film sideways (lying down is the easiest way). Do left and right work as well as up and down?

4) Look at your entire film in reverse. Does Effect stem solidly from Cause? Do Alpha and Omega have good connections? Does the musaic hold together backwards?

*

A film is never finished, it is only abandoned. But if we are wise we are not expecting perfection anyway, since nothing in life is perfect, art included. All we alchemists can hope for: to arrive somewhere close to our original vision. Or, at some more astonishing place than we ever imagined.

“Perfection of thing is threefold; first, according to the constitution of its own being; secondly, in respect of any accidents being added as necessary for its perfect operation; thirdly, perfection consists in the attaining to something else as the end.” – Thomas Aquinas

*

The value of pursuing any art is to live life more ineffably. Or, as Spengler put it, ‘we can understand the world only by transcending it.’

My life has prospered when I have remembered to pursue the Essential, the Eternal, and the Ecstatic.

One thought on “The Big Joy of Poet and Filmmaker James Broughton”